History › Community resettlement

Community resettlement

Port Moresby’s urbanisation challenge

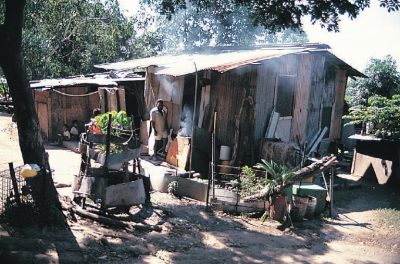

The growing issue of unplanned urbanisation, due to the mass migration of people relocating from rural villages to urban centres over the past three decades, has contributed to a rapid growth of urban squatter settlements. The scarcity of state land also means that informal settlement communities will increasingly need to be relocated due to development projects. Such was the situation facing PHDC when it acquired the land at Paga Hill via a 99 Year State Lease.

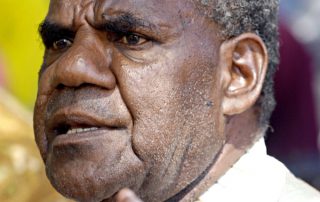

Squatters in Port Moresby circa 2005. Credit: Stephen Codrington

Intent

Paga Hill Estate is set to present a modern and progressive image of the country to the rest of the world. We have always considered a peaceful relocation of the informal settlement as a positive step towards realising this vision. Given the prevalent issues of land scarcity and unaffordability, we took it upon ourselves to acquire land for the settlers to relocate to, providing financial, logistic and other assistance to facilitate the move.

Consultation with relocating settlers

The relocation initiative

Despite a difficult process, with long and costly delays due to a succession of legal challenges, we achieved the best possible outcome within the legislative and regulatory framework at the time. The settlers we relocated were given secure tenure over their own parcel of land, which some have since sold.

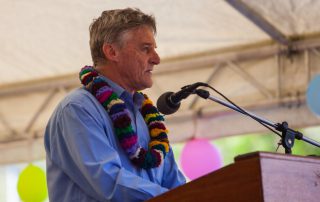

Whilst the PNG Police’s execution of court-issued eviction orders in May 2012 was done in a way not unfamiliar in PNG, these events were not within our control. Even so, Assistant Commissioner and NCD-Central Police Commander Mr Jerry Frank took the relocation site’s handover ceremony as an opportunity to express regret over how the relocation transpired. Also present at the handover ceremony was the United Nations Resident Coordinator Mr Roy Trivedy, who acknowledged the significance of these unprecedented efforts in PNG, commending Paga Hill Development Company on the landmark achievement.

We sincerely hope that the lessons learned from the relocation of the Paga Hill settlers will benefit the broader urbanisation process in Papua New Guinea.

Speech by Mr Roy Trivedy, UN Resident Coordinator in PNG, at the relocation site handover, 1st October 2014

FAQs

The former settlers had no legal right to reside at Paga Hill and knew they were illegally squatting.

Some claim that the settlers had an agreement with ‘customary landowners’ to reside at Paga Hill, however this is vehemently denied by the Motu Koita Assembly, who are traditional owners of all Port Moresby, as well as National Capital District more broadly. The fact is, Paga Hill was a national park and therefore State Land until PHDC applied for its rezoning, first securing a 5 Year Urban Development Lease in 1998, and ultimately a 99 Year State Lease in 2000.

As local Member of Parliament between 1997 and 2012, Dame Carol Kidu is quoted as repeatedly notifying the Paga Hill squatters of their requirement to eventually move. The community did not have power, sewer or water infrastructure, knew they were illegally squatting and knew they would ultimately have to relocate.

PHDC has evidence of extensive consultation with the former settlement dating as far back as 2002. Towards the end of 2011, as PHDC firmed plans to commence development at Paga Hill, efforts to engage the settlement increased in intensity and various solutions were pursued for their harmonious relocation.

As the time to commence construction neared, PHDC increased consultation activities in mid to late 2011. This would eventually result in an agreement to peacefully relocate, which was signed by the settlement’s longstanding leadership and recognised by the courts in the form of a Consent Order. For the courts to do this, extensive evidence of community-wide consultation and agreement was provided.

Every eviction was extensively communicated. In fact, the first eviction of 12th May 2012 took place after the courts overturned a stay order that had been obtained by the settlers.

Despite not being legally required to do so, PHDC carried out the first privately funded and humane resettlement of an illegal squatter community in PNG, receiving United Nations praise for this landmark achievement.

The court-recognised Consent Order makes reference a package of assistance PHDC would provide to settlement households in order for them to relocate, but this was not the only assistance provided.

As part of PHDC’s efforts to negotiate a harmonious relocation in 2011, settlement leaders first requested funds to acquire a preferred site they had identified. Despite PHDC transferring funds, for whatever reason the monies did not result in the land being secured. Settlement representatives then informed PHDC that the settlement households would be happy to receive cash to fund their own relocation. Given the low success likelihood of this approach PHDC then set about finding a viable relocation site, settling on a similar sized parcel of customary land at the suburb of Six Mile. PHDC would then commission a master planning exercise for what the relocated community would eventually name ‘Tagua Village’, preparing the land for the erection of homes, as well as supplying the site with basic infrastructure and temporary shelter. PHDC then undertook a demographics survey to categorise the informal dwellings of each household, which would then determine the level of financial assistance provided, as per the terms of the Consent Order.

In the months leading up to the Consent Order’s agreed relocation due date, PHDC provided vehicles and approximately 20 staff at Paga Hill each day, assisting with the dismantling of informal dwellings and their relocation to Tagua. PHDC also provided financial assistance, literacy and business training, as well as community governance training and support at Tagua. This exercise was carried out with the help of an experienced community development consultant, a seasoned United Nations professional, as well as Dame Carol Kidu, a highly respected former politician and humanitarian. Each relocated household would also be the recipient of donated land at Tagua – in what is a transformative outcome, previously illegal squatters were now recognised landowners.

Despite a subset of the settlers challenging their requirement to relocate, delaying PHDC access to Paga Hill by a number of years, PHDC remained true to its initial offer of support and donated land.

PHDC adhered to Amnesty International and United Nations guidelines at all times and would ultimately receive United Nations acclaim for what was ultimately achieved.

At every stage PHDC has acted in accordance with PNG law. At every stage, the settlers were extensively consulted and were afforded legal representation. At the point of every eviction, the settlers had access to temporary accommodation, as well as the land donated to them by PHDC.

At every point the settlement had access to legal representation. That the settlers were able to stay eviction orders (on multiple occasions), challenge the validity of our title and their requirement to relocate all the way to the Supreme Court is evidence of this.

At no point has a lack of legal representation hindered their ability to stay at Paga Hill. The facts, as upheld by multiple court decisions, remain that the settlement was adequately consulted and were knowingly illegally squatting at Paga Hill.

An attempt by a group of former settlers to seek compensation was comprehensively dismissed by the courts in 2016 for having no basis. Despite not being required to do so, and in a first for the country, PHDC had provided extensive relocation support and was commended by the United Nations for what was achieved. Any suggestion that compensation is somehow outstanding is misleading to the former settlers, defamatory to PHDC, and may well be in contempt of court given the processes already concluded by the District, National and Supreme Courts of PNG.

At no stage have the courts ruled in favour of the settlers.

Every decision by the District, National and Supreme Courts of PNG has maintained that PHDC is the legitimate titleholder to Paga Hill, that the settlers were extensively consulted and that they were knowingly illegally squatting.

Some persist in misrepresenting a Supreme Court decision that found a small area of land evicted on 12th May 2012 was not part of PHDC’s title. These same people claim that this was some form of victory for the settlers, and that their ultimate eviction was a ‘miscarriage of justice’. This false misrepresentation is solely for the purpose of pursuing a marketable narrative for a film, together with the promotion of those associated with it. Furthermore, PHDC argues that this claim is contemptuous, which is the subject of proceedings sub judice in PNG against the filmmaker and its protagonist.

The facts are clear: while the Supreme Court ruled that a small portion of the evicted area on reclaimed land at Paga Hill’s waterfront was outside of PHDC’s title, no alternate title existed and to the best of anyone’s knowledge, that area constituted part of PHDC’s title. Furthermore, the Supreme Court upheld that the settlers were illegally squatting and would have to relocate.

The land in question, which is at Paga Hill’s waterfront, had otherwise always been considered part of PHDC’s title. The Section 81 Agreement (between the city authority NCDC and PHDC) of 2000 makes provision for a ring road around Paga Hill’s waterfront. PHDC submitted designs for a ring road in early 2011, which featured a road alignment through this same portion of reclaimed land, and were eventually approved prior to the first evictions taking place. Whilst the settlers sought to remain at Paga Hill on a technicality, the Supreme Court maintained that they were illegally squatting, hence why they were subsequently evicted by the State and its contractor as part of the development of the ring road about Paga Hill.

PHDC assisted in the relocation of those settlers living above the line of the to-be ring road around Paga Hill. The land along Paga Hill’s waterfront was compulsorily acquired by the State, with those living there evicted by the city authority and its road contractor Curtain Bros.

PHDC relocated those within its responsibility to Tagua Village at Six Mile, with the site officially handed over in October 2014 to United Nations acclaim. Many households at Tagua have since sold their land, with those currently residing at Tagua no longer representing the relocated community. More than four years after the site’s handover, PHDC is not aware of the status of each of the relocated households.

There is much to be learned from our experience and we sincerely hope it can be leveraged.

PNG has countless informal settlements that stand in the way of urbanisation, and forced evictions are commonplace. PHDC values human rights and our efforts throughout this entire process, spanning more than ten years, are testament to this. Our landmark efforts to humanely resettle the illegal squatter settlement are the first of its kind in PNG.

We sincerely hope our experience can be leveraged. For example, there is no process for converting customary land to state leasehold, which is what led to us utilising Land Use Agreements to confer ownership to resettled families. Also, communities like the relocated settlers at Tagua remain formally unrecognised by government frameworks and regulations. Similarly, there is much to be learned from the current state of the relocation site; despite being handed over in October 2014 to UN acclaim, we believe that many of the former settlers have failed to meaningfully move on with their lives, or at least have failed to build on their donated land. We believe this has something to do with frequent calls to action for compensation, with the former settlers being led to believe an imminent windfall is in order.

PHDC has extended offers to collaborate with Amnesty International, United Nations and FHI360 to overcome urbanisation challenges and learn from our experience, but none have taken up the offer.